Museum talk marks 200 years since ‘massacre’

By Sue Hughes | For The Times-Post

PENDLETON — “I don’t know why Hollywood never made this a movie,” David Murphy said Sunday about the events surrounding the murder of nine American Indians in South Madison County 200 years ago, and the subsequent trials and executions of three white men.

Murphy, an Anderson University history professor, talked about what is often referred to as the Fall Creek Massacre. He spoke in the Community Building at Falls Park on Sunday, as part of Pendleton Historical Museum’s speaker series.

Marla Fair of Johnston Farm and Indian Agency in Piqua, Ohio, spoke about John Johnston, a U.S. Indian agent who was involved with the trials.

About 60 people attended the event. The presentation was billed by the museum as a day of remembrance, for a relatively well-known chapter of local history memorialized in markers in Falls Park and elsewhere in South Madison County.

Murphy, who wrote the book “Murder in Their Hearts: The Fall Creek Massacre,” published by Indiana Historical Society Press, said near the beginning of his presentation that many stories about what occurred that day are not necessarily accurate.

“Stories get passed down from generation to generation, and things get changed,” he said. “We can’t be absolutely certain of what happened, the tribes or the Indians’ names.”

As Murphy related the events, on March 22, 1824, a group of white men who had been drinking all weekend decided they did not want the American Indians in the area. The men were led by Thomas Harper. Harper, a known violent young man who was “infused with anger toward the Indians,” convinced James Hudson, John Bridge, his son John Bridge Jr. and Andrew Sawyer to help him attack the camp of the Indians.

The camp was located near what is now Markleville.

The settlers first killed two American Indian men, known as Logan and Ludlow, he said.

They lured Logan and Ludlow into the woods with the promise of 50 cents if they helped find some lost horses, Murphy said. Ludlow was the first to be shot; after they killed Logan, the men went back to the camp and killed the women and children there.

With the exception of Harper, the men were soon arrested and detained. Harper escaped and was never seen again.

James Hudson was the first of the men to be found guilty. The jury deliberated for less than an hour. Although he appealed to the Indiana Supreme Court, his verdict was upheld, and he was hanged in January 1825.

The other three men were also found guilty and were scheduled to be hanged in June 1825.

Someone started a petition to save the life of Bridge Jr., and with 110 signatures it was sent to Indiana Gov. James Brown Ray, Murphy said. Ray came riding up at the last minute on a horse and said, “Only two men can save you now — God and Gov. Ray,” and with that the young man was pardoned.

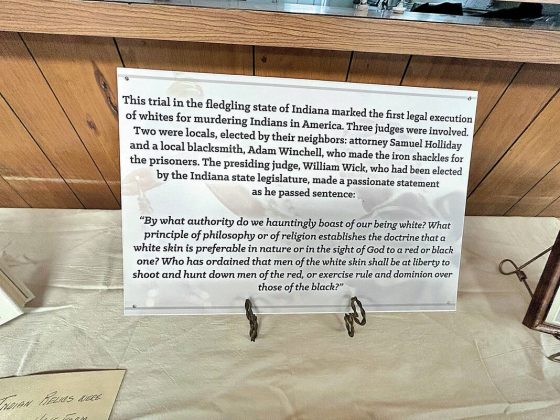

“It was very unusual for a white man to be convicted of murdering an Indian; they would almost always get a manslaughter charge,” Murphy said. “That is what makes this event so important, it is the only case I have read where this has happened.

“I can’t understand why it is not more widely known,” Murphy added.

Murphy, who is originally from Illinois, said he lived in Indiana for 10 years before it was brought to his attention by one of his students.

“To keep the Indians from seeking their own revenge for the massacre, they were invited to watch the hanging,” Murphy said.

In response to a question from the audience, Murphy said although he has looked, he has not been able to find where any of the men were buried.

Murphy concluded by saying, “The one time we did the right thing, why is so little known?

“This should be a movie!”

Fair expressed similar dismay about the relative obscurity of John Johnston.

“Why doesn’t anybody know about this guy?” she asked.

Probably, she said, because “he was a good honest man who took care of his family and never had a scandal.”

Johnston was an Indian agent in Fort Wayne before moving his family to western Ohio.

The sheriff in the area where the killings happened knew Johnston would be able to keep the American Indians calm.

“They knew they were sitting on a powder keg,” Murphy added. The people in Indiana knew Johnston was not prejudiced toward the Indians, he said.

“He liked them and often had them as guests in his home,” Fair said. “He considered them his personal friends.”

Fair said Johnston wrote in his journal, “a most shocking murder was committed in Madison County Indiana.”

Johnston was chosen for the job even though there were agents closer to the site.

Murphy said Indian agents were not always honest and would sometimes steal items meant for the Indians.

The trials lasted a year and a half, and during that time Johnston would ride between his home in Ohio and Indiana as needed.

Karyn Ledbetter, social media director at the museum, said Sunday’s talk came about because “I was looking at the marker that shows where the men were hanged, and I thought we should do something to remember that day.”

The 200th anniversary of the massacre is March 22.

Many of the attendees had a personal connection or interest in the story.

“I am related to the Keeslings — my ancestors owned that land (where the murders purportedly took place),” Diane Michael said.

Another attendee, Eric Hensley, said, “I grew up in Pendleton, I am interested in history, and I collect Indian artifacts.”

Carolyn Brewer — who with her sister, Connie Bullington, are the current owners of the property where the murders are thought to have happened — said she found the presentations interesting.

“I always like to hear what they have to say,” she said. “Other people always have different perspectives on how they view things.”

Also, she added, Fair shared some information that was new to her.

“I didn’t know that much about Johnston,” she said.

Video of the talk will be available on the museum’s website and Facebook page, Ledbetter said.

Community Editor Scott Slade contributed to this story.